This is the

first article of a series about the sovereignty dispute over the islands in the South Atlantic called Falklands by the British, who control

and inhabit them, and Malvinas by

Argentina,

the country that contests their ownership. I chose this topic because of my

enthusiasm for history, the fact that I am Argentine, and because on this day,

30 years ago, an Argentine force took over the islands’ capital, starting the

regrettable 1982 Malvinas/Falklands crisis. This commemoration motivated the stamp shown on the right, issued last Saturday.

This will hopefully be a four-post series. There are philatelic materials and stories that I will present but, this time, please allow me to use philately to contextualize history [1] rather than doing it the other way round, as usual.

This will hopefully be a four-post series. There are philatelic materials and stories that I will present but, this time, please allow me to use philately to contextualize history [1] rather than doing it the other way round, as usual.

In her address to the U.N. Security Council

during the conflict, U.S. Ambassador Kirk Fitzpatrick summarizes the long, legal dispute that preceded the 1982 war:

We have all come to appreciate how deep the roots of the conflict are. Britain, in peaceful possession of the Falkland Islands for 150 years, has been passionately devoted to the proposition that the rights of the inhabitants should be respected in any future disposition of the Islands. No one can say that this attitude, coming from a country that has granted independence to more than 40 countries in a generation and a half, is a simple reflex to retain possession.

Yet know how deep is the Argentine commitment to recover islands they believe were taken from them by illegal force. This is not some sudden passion, but a long-sustained national concern that also stretches back 150 years, heightened by the sense of frustration at what Argentina feels were nearly 20 years of fruitless negotiation.[2]

The 150-year span, referred by Fitzpatrick,

started with the events of January, 1833, when two British warships arrived at

the islands, and removed the Argentine authorities that had been sent to repair

the damage that a warship from the U.S. had done to the settlement

founded by Louis Vernet.

Vernet was a Hamburg-born merchant

of French Huguenot descent, married to a lady of the River Plate region. In the

early 1820s, while he was operating a cattle business in the province of Buenos Aires,

a relative-in-law, Jorge Pacheco, approached him with a proposal that probably caught

his ambitious, entrepreneurial eye.

The government [3],

owing Pacheco money in exchange of services rendered during the war for

independence, had offered him a grant for the exploitation of wild cattle at

Malvinas/Falklands, an activity that the Spanish undertook before abandoning

the islands in 1811. Pacheco took the proposal to Vernet, who saw an economic potential, not just from cattle but also from fishery and support to sea traffic, the

latter being numerous because the islands were on the main sea route between

the Atlantic and Pacific oceans (before the opening of the Panama Canal). [4] Or at least he argued about this potential in 1832, in a report he wrote for the American Chargé d’Affairs where, among other things, he questions the reasons, of an economic nature, that the British were giving to justify their abandonment of the islands decades before.

[5]

As a well-read person, he also must have known that a proper occupation of the islands would strengthen the sovereignty that Buenos Aires claimed shortly before. Associated with Pacheco, they accepted the offer and enticed the government with the sovereignty argument to raise the ante, obtaining permission to re-found the old Spanish settlement. Equipped with those concessions and ships, hardware and men funded by Vernet, they tried to establish a settlement in 1823, but failed, as they did on another expedition in 1824, which was commanded by Pablo Areguati, who was designated commandant of the islands by Buenos Aires in 1823 [6].

However, Vernet succeeded in 1826, after purchasing Pacheco’s part, therefore rising the

first Argentine permanent settlement on the islands [7]

since they were claimed, in this country’s name, by Captain David

Jewitt in 1820 [8]

[9], on

the grounds of them being inside the sphere of the former Spanish colony and,

as a consequence, now within the borders of the independent nation that had

emerged from it. [10] [11]

This originates from a legal principle called uti possidetis juris, which was an important criterion to settle the borders of nascent states. [12]

European nations were not formally bound by it but they normally respected it, customary practice being an important source of international law. During their wars for independence, the nations of the Americas disputed their territory with their

former colonial powers, not with unprovoked third nations that felt

that they had been given free rein to grab a piece. Moreover, uti possidetis juris, when applied to frontiers that were already international before the advent of the new state, was considered as a derivation of a preexisting general law of state succession by the International Court of Justice in its judgement for the frontier dispute between Burkina Faso and Mali:

[T]he [uti possidetis juris] principle is not a special rule which pertains solely to one specific system of international law. It is a general principle, which is logically connected with the phenomenon of the obtaining of independence, wherever it occurs. [...] Its purpose, at the time of the achievement of independence by the former Spanish colonies of America, was to scotch any designs which non-American colonizing powers might have on regions which had been assigned by the former metropolitan State to one division or another, but which were still uninhabited or unexplored. However, there is more to the principle of uti possidetis than this particular aspect. The essence of the principle lies in its primary aim of securing respect for the territorial boundaries at the moment when independence is achieved. [...] The territorial boundaries which have to be respected may also derive from international frontiers which previously divided a colony of one State from a colony of another, or indeed a colonial territory from the territory of an independent State, or one which was under protectorate, but had retained its international personality. There is no doubt that the obligation to respect pre-existing international frontiers in the event of a State succession derives from a general rule of international law, whether or not the rule is expressed in the formula uti possidetis.

Gustafson makes the point that, if uti possidetis juris were not

recognized for the Argentine actions starting in 1820, the principle of

acquiring res nullius may be, given

that Spain

abandoned the islands in 1811. [13] The Law of Nations considered that res nullius, or nobody's property, was available for whom properly claimed and occupied it. I find the

application of res nullius to be arguable for this case, given that Spain’s absence was short and

justified by the war with its former colonies, although the loss of the Vice-Royalty

was reason to believe that the Iberians would not be interested

in exercising sovereignty anymore. But Gustafson’s point is that, if uti possidetis juris is rejected on the

grounds of Spain losing

possession in 1811 when she abandoned the islands, then Argentina would

earn rights by virtue of acquisition of res

nullius. The other possibilities are to consider the islands in 1820 to be

Spanish or to acknowledge competing claims if there were ones with merits at that

time. More about this in the next post.

In 1828, Vernet extended his

concessions by obtaining further land from Buenos Aires [14],

and moved his family to the islands. To read more about his project, I

recommend the aforementioned report, written by himself in 1832 to present his

case to the American authorities, after the destruction of presumably much of his

settlement by Captain Silas Duncan of the USS Lexington [15]. It is a well-written, albeit long, piece where he details the story of the Argentine presence in the islands, and argues thoroughly in favor of her rights to them. Needless to say, it is the version he put forward in 1832 as a stakeholder, not an historian, yet I find

it compatible with what I have read from authoritative sources.

Contemporary accounts about Vernet's settlement were also given by two Captains of the Royal Navy: Robert FitzRoy and L. B. Mackinnon. FitzRoy writes:

To show how well the little colony, established by Mr Vernet at Port Louis, was succeeding, prior to its harsh and unnecessary ruin by Captain Duncan, we give an account of it by a visitor: “The settlement is situated half round a small cove, which has a narrow entrance from the sound. This entrance, in the time of the Spaniards, was commanded by two forts, both now lying in ruins; the only use made of one being to confine the wild cattle in its circular wall; when newly brought in from the interior. The governor, Louis Vernet, received me with cordiality. He possesses much information, and speaks several languages. His house is long and low, of one story, with very thick walls of stone. I found in it a good library of Spanish, German, and English works. A lively conversation passed at dinner; the party consisting of Mr Vernet and his wife, Mr Brisbane, and others. In the evening, we had music and dancing. In the room was a grand piano forte. Mrs Vernet, a Buenos Ayrean lady, gave us some excellent singing, which sounded not a little strange at the Falkland Isles, where we expected to find only sealers.

“Mr. Vernet’s establishment consisted of about fifteen slaves, bought by him from the Buenos Ayrean Government, on the condition of teaching them some useful employment, and having their services for a certain number of years, after which they were to be freed. They seemed generally to be from fifteen to twenty years of age, and appeared contented and happy.

“The total number of persons on the island consisted of about one hundred, including twenty-five gauchos and five Indians. There were two Dutch families (the women of which milked the cows and made butter) ; two or three Englishmen; a German family; and the remainder were Spaniards and Portuguese, pretending to follow some trade, but doing little or nothing. The gauchos were chiefly Buenos Ayreans; but their capataz or leader was a Frenchman.”

Such was the state of Vernet’s settlement a few months before the Lexington’s visit; and there was then every reason for the settlers to anticipate success, as they, poor deluded people, never dreamed of having no business there without having obtained the permission of the British Government.

Mackinnon's work corresponds to his 6-month residence at the islands in 1838, shortly following the expulsion of the Argentine authorities and before Britain had established its authority or there was any significant new immigration. In his depiction he narrates how Buenos Aires granted land to Vernet, 'who, after surmounting many difficulties, and under several privations, was advancing prosperously in his attempt at colonization', also describing the drying establishment where 'Don Louis Vernet, the governor, under the Argentine Republic, prepared this fish for the Brazilian market' and the numerous cattle that were tamed by Vernet's gauchos.

Jewett's and FitzRoy's accounts are reproduced in Ellms' Robinson Crusoe’s own book [16], published in the US in 1848. All of these texts are available for online reading.

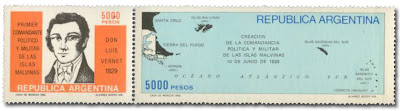

Vernet was commemorated twice inpostal issues from Argentina.

Firstly on a pair (Sc. 1365 and 1366), shown on the right, that was issued on June 12, 1982,

during the last days of the war. A quite ugly pair, if you ask me. I

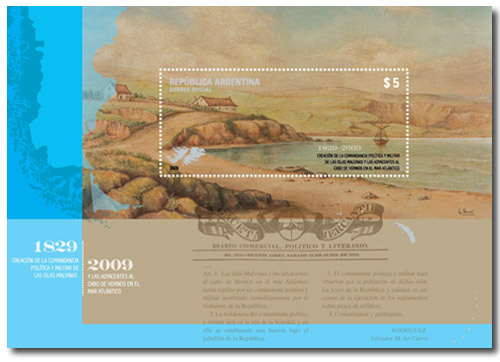

prefer the second pair, issued in 2009, shown in pictures above, comprised of a stamp

and a miniature sheet. These reproduce oil paintings by

Luisa Vernet Lavalle Lloveras, who I believe was Vernet’s daughter although I couldn’t

confirm this. The stamp shows a portrait of the Governor, while the sheet

depicts the first houses built in stone in the settlement at the Island of Soledad,

or East Falkland according to Britain.

Vernet was commemorated twice inpostal issues from Argentina.

Firstly on a pair (Sc. 1365 and 1366), shown on the right, that was issued on June 12, 1982,

during the last days of the war. A quite ugly pair, if you ask me. I

prefer the second pair, issued in 2009, shown in pictures above, comprised of a stamp

and a miniature sheet. These reproduce oil paintings by

Luisa Vernet Lavalle Lloveras, who I believe was Vernet’s daughter although I couldn’t

confirm this. The stamp shows a portrait of the Governor, while the sheet

depicts the first houses built in stone in the settlement at the Island of Soledad,

or East Falkland according to Britain.

This pair was issued on the occasion

of the 180th anniversary of a decree dated June 10, 1829, that

appointed Vernet, then Director of the settlement, as Civil and Military Commandant

of the Islands and their adjacencies

[17], therefore empowering him with a public title to complement his commercial concessions. In his

own words, this was done to ‘[impose] on him the duty of carrying into effect

the regulations relative to the Seal-fishery’ because ‘The depredations of

Foreigners on the Coasts still went on, and there was no force in the Colony

capable of restraining them, nor was there any public Officer to protest

against them. This state of disorder obliged me to require the Government to

adopt some measures.’ [18]

At his return to the islands, the new

commandant began his efforts to enforce sealing regulations approved by the

Argentine government. In one attempt, he seized two American vessels that, as he argued, had

breached those norms in spite of previous warnings. Vernet sailed to Buenos

Aires with one of the captains, to try them at court.

Unfortunately, the U.S. Consul at the Argentine capital, George Slacum, who was

inexperienced and, according to Peterson [19], ‘a tactless diplomatic novice’,

regarded the seizure as an act of piracy, encouraging Silas Duncan, the captain of the USS Lexington, to sail to the islands. The Lexington was a warship

just passing by the city. Duncan

sailed supposedly to rescue a few American citizens who were

stranded as a result of the seizures, but instead he took his time to perform

other matters. Among these, to cause havoc on Vernet’s settlement and evict many settlers, with a share of violations to human dignity. [20]

Buenos

Aires made Slacum responsible for the destruction and rejected his offices. U.S. President

Jackson sent Francis Baylies to discuss the case, appointing him as Chargé

d’Affairs. Baylies defended Duncan’s

actions and demanded reparations from the seizure, only to be presented with

the Argentine case for the islands, explained by Vernet in the aforementioned report

of 1832. The Chargé d’Affairs returned the report, arguing that he was not

entitled to discuss those kinds of matters, and promptly returned home,

disregarding Argentine requests to continue talking. John Quincy Adams, who was former U.S. president at the time and a

political opponent to Jackson, not being fond of

Baylies whom he regarded as ‘one of the most talented and worthless men in New

England’, summarizes the exchange in his memoirs: ‘Jackson, to appease him, gave [Baylies] as a

second sop the office of Chargé d’Affaires at Buenos Ayres. He went there;

stayed there not three months —just long enough to embroil his country in a

senseless and wicked quarrel with the Government; and, without waiting for

orders from his Government, demanded his passports and came home. Nothing but

the imbecility of that South American abortion of a state saved him from indelible

disgrace and this country from humiliation in that concern.’ [21]

These American reactions, including John Quincy Adams' words, are better understood if we consider Jackson's inclination towards 'gunboat diplomacy' as well as his 'spoils system', which meant that government jobs were assigned in reward for electorate services, no matter how unfit for the job the candidate was. These characteristics were heavily criticized by Jackson's opponents, which included previous president Adams.

Before departing, Baylies’ renamed

Slacum as the American head diplomat in Argentina,

but Buenos Aires

once again did not accept his offices, arguing that he was a transgressor of

justice taking refuge at the American residence. Thus, Slacum departed with

Baylies. The U.S.

did not officially appoint a replacement, and relations between these two

countries remained severed for more than a decade.

In the meantime, Buenos Aires had appointed a new governor for the islands, who was sent there with some personnel on board clipper Sarandí, depicted in this 1977 stamp (Sc. 1146). They were commissioned to restore order and rebuild the garrison. The settlement had suffered, not just from destruction and eviction of some settlers, but from the

uncertainty caused by the incident.

Despite those reconstruction efforts, the

scene was set for a forceful action by Britain. We can speculate on several reasons for this. On the one hand, an

invasion had turned to be more tolerable to the eyes of the world, due to the

state of disarray in the settlement, particularly after the new governor was killed by some rebels in his crew. But another element was probably more

important. However desirable the islands were, one of the deterrents to a high-handed

act from the U.K. was the Monroe doctrine, which indicated that the US would respond to European attempts of conquest in the Americas.

But the Lexington incident was a risk for American diplomacy, which presumably inclined her to accept British arguments based on a history of discovery, first landing and occupation that I will elaborate in the next post. Moreover, some commercial interests in the US had not liked Vernet’s determination to enforce the rule of law. The Commandant had justified them on the grounds of regulating fishing to preserve the population of seals, but some claimed they constituted an attempt to retain privileges unjustifiably. Among them, Greenhow, who writes, in a defense of the American position that was contemporary with the events

[22]:

Had the Buenos Ayreans been content to settle on the islands, without seeking to deprive others of advantages which they had no means of appropriating to themselves, and which, by reason, justice, and the consent of all civilized nations, were common to all, it is more than probable that their rights thus exercised would have been tacitly recognized, and that their establishment might have become profitable to themselves, and beneficial to all other nations But their imprudent and rapacious conduct, in attempting to revive the unjust and obsolete prohibitions which Spain had been unable to enforce, drew down upon them the indignation of more powerful states, and subjected them to humiliations for which they have no claims to redress. [23]

The next post discusses the 1833 takeover and its interpretation from a legal point of view. Hopefully,

the series will have a third post with a chronicle of the dispute from 1833 to

1982, and a fourth about the 1982 war. I may get hold of and publish,

anytime soon, high-resolutions scans of some of the stamps showcased here. As always, comments are welcome.

The next post discusses the 1833 takeover and its interpretation from a legal point of view. Hopefully,

the series will have a third post with a chronicle of the dispute from 1833 to

1982, and a fourth about the 1982 war. I may get hold of and publish,

anytime soon, high-resolutions scans of some of the stamps showcased here. As always, comments are welcome.

[1] I believe the historical facts are pretty much agreed

at an authoritative level, and that these blog entries tell that version, or at

least they are compatible with it. I don’t mean to say that there are no

discrepancies, but, at a learned level, these are mostly in the weight

attributed to each argument, not so much on the historical events. Yet, there

is a harder discourse in favor of the British position, that is not written in

authoritative literature but in the English version of Wikipedia, as well as in

a few texts that rank well on Google Search. Those articles generally use genuine

references, which lead some readers to believe that they have the rigor of

serious academic studies, but there is a manipulative selection of the facts

mentioned, a fallacious logic in some of the reasoning derived from those

facts, and a questionable choice of sources, frequently referencing each other

instead of resorting to authoritative work.

I

think this relates to the problems of direct democracy, akin to the system used

in Wikipedia and Google Search rankings, compared to indirect democracy. These

problems were explained by the founding fathers of the United States in the Federalist

Papers. In the argumentative line that would lead to the preference for

indirect democracy, Madison warned against the dangers of factions, which he

defined as ‘a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority

of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or

of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and

aggregate interests of the community.’

Despite not being organized as such, in

this case the ‘faction’ would hypothetically be composed of islanders, and other

English-speaking supporters of the British case, who are emotionally invested in

the dispute, and probably outnumber those bilingual Argentinians, and other

English-speaking sympathizers of the Argentine case, who are learned and

passionate enough about the subject to sustain ‘edit wars’ with them on the

English-language Wikipedia. The balance between these groups, or its lack thereof, is critical because they are much more motivated

than neutral Wikipedia editors. Besides, the first group probably has higher

influence in English-language websites than those in the second, therefore being able to place links to

pieces that earn their sympathy, particularly those that are simple and emphatic though lacking in rigor, linking being

crucial to rankings on Google Search.

As a result, the group imposes its beliefs in media

that employs some sort of direct democracy,

even with no bad faith involved. I would not expect anything better

from the Spanish-language webspace, favoring the other side of the dispute. The

bottom line is that Wikipedia and those kinds of webpages seldom provide proper summaries

for a controversial subject like this. They should be taken with a healthy dose

of critical thinking, comparing facts and conclusions with authoritative work. Unfortunately,

it looks like the general public attributes summarization quality to them even

for these kinds of matters; and it seems that, regrettably, some journalists do

the same.

[2] Fitzpatrick, K.; “Seeking Peace in the

Falklands”; U.N. Security Council, May 22, 1982, in Kirkpatrick.,

J. J.; Legitimacy and Force, Vol 2:

National and International Dimensions; Transaction Books, NB, and Oxford, U.K.;

1988; p. 221

[3] Argentina had proclaimed its independence in 1816 and was formally

recognized by Britain in 1823 and, with more precision, in

1825. It typically used the name ‘United Provinces of the River Plate’ at

the time, though the names ‘Argentines’ and ‘Argentine Republic’

were valid since before its independence. During much of the 1820s, the nation

suffered civil wars, as its regional leaders would not agree on a system of

government. Yet, they did agree on Buenos

Aires being responsible for the nation’s foreign

policy during those turbulent years. So did foreign nations, most importantly Britain in

virtue of the aforementioned recognition, which was signed during some of the

worst moments of the civil war. Moreover, the national identity was always present

in the minds of the local leaders, as evidenced by various treaties that they

signed, with the exception of a short-lived secessionist attempt in Entre Rios.

Some texts on the Internet challenge this historiography (see footnote 1) but this is not an issue at a learned level.

[4] The coasts of the nearby mainland were less viable for

settling due to Amerindian attacks. Darwin

comments on this in The Voyage of the Beagle, p.

174. However, Falkner argues that, considering the convenience of wood, water

and soil, the mainland coast would have constituted a better place for a colony

at the passage between the southern seas (cited by Fitzroy, p. 137).

Moreover, Fitzroy comments (in Narrative of the

Surveying Voyages of His Majesty's Ships Adventure and Beagle, vol. 2,

p. 169) that some natives may have been well disposed towards a ‘white’

settlement in Patagonia.

[5] ‘A Nation accustomed to make the greatest

sacrifices for obtaining and securing every thing that can be of interest to

her trade—a Government which never resists that which is called for by a

majority of its Subjects, and whose policy tends principally to the

aggrandizement of its commerce—a Nation which had shown itself irritated to an

extraordinary degree on being despoiled of Port Egmont [the British settlement

on the islands in the 18th century], and which had not hesitated to expend, in a

few months, nearly 20,000,000 of dollars in warlike preparations on that

account—an opulent and enterprising mercantile Nation, which had so much

occasion for that Place, as is proved by the numerous Vessels belonging to her,

which, from that time, up to the present, have frequented the Islands, either

to take in provisions, or for objects connected with the Fisheries—such a

Nation, having just obtained pacifically, and without expense, the enjoyment of

those advantages for ever, suddenly to abandon her Possessions, solely for the

miserable saving of the expense of their support, when merely the produce of

the Fisheries would more than repay the expenses of the Establishment—abandon

them from motives of economy, without leaving even a Vessel, or a few men,

notwithstanding her riches, her numerous Navy, and her excessive

Population—abandon them in silence when she might have spoken openly, and it

was so much her interest to do so! This, Excellent Sir, 1 can say, with

confidence, is impossible. To render it credible, it would be necessary they

should bring forward proofs and deeds as irrefragable as is this fact, that the

English did entirely abandon the Malvinas.’ Vernet (see footnote 15), pp.

409–410.

[6] Pepper and Pascoe (see footnote 1) claim that Areguati was not named but that his

appointment was only requested. To support this assertion, they cite a decree

which does not resolve on his appointment, and a book that I didn’t have the

chance to read. Yet, he could have been named by a posterior decree. I don't remember, from authoritative literature, any challenges to Areguati’s appointment, which was confirmed by at least Fitzroy in 1839, Greenhow in 1842, Gustafson, Hope and Peterson, plus, if snippets on Google Books don't mislead, by Boyson, Strange, Dolzer, Howgego, Hoffman and Gough too.

[7] It has been argued (see footnote 1) that many settlers were not Argentine, as if that

would weaken the Argentine status of the settlement. But what is legally

relevant is that the authorities were acting under Argentina,

applying laws and legal instruments emanating from Buenos Aires, and the settlers consented to

that rule. It is acceptable and normal that a nation welcomes foreign subjects

to an otherwise deserted, or loosely populated, portion of its territory.

Particularly when it is young and desires immigration, as it was the case with

Argentina, more so for its insular and coastal territories considering that the

local creole were not seafaring

people. It does not imply any loss of sovereignty. Vattel writes: ‘When there

is not this singular circumstance [of a nation deciding to keep a portion of

her territory in desert and uncultivated form], it is equally agreeable to the

dictates of humanity, and to the particular advantage of the state, to give

those desert tracts to foreigners who are willing to clear the land and to

render it valuable. The beneficence of the state thus turns to her own

advantage; she acquires new subjects, and augments her riches and power. This

is the practice in America;

and, by this wise method, the English have carried their settlements in the new

world to a degree of power which has considerably increased that of the nation.

Thus, also, the king of Prussia endeavours to re-people his states laid waste

by the calamities of former wars.’ Vattel, E. de; The Law of Nations; (1758); II.VII.87;

Translation by Chitty, J.; Johnson & Co., PA

[8] Weddell,

J.; A voyage towards the South Pole:

performed in the years 1822-24 (1825); p.103–112. Jewitt was an

American sailing under Argentine colors at the time. The nascent Argentine navy

normally hired foreign captains because the local creoles were not seafaring people; a notorious example being an

Irishman called William Brown, commemorated in the stamp on the left, who was her greatest naval hero at the war for

independence. A few years later Greenhow22 wrote about Weddell’s narrative, that he ‘ridicules

the whole proceeding; insinuating his belief, that Jewett had merely put into

the harbor in order to obtain refreshments for his crew, and that the

assumption of possession was chiefly intended for the purpose of securing an

exclusive claim to the wreck of the French ship Uranie, which had a few months

previous foundered at the entrance of Berkeley Sound.’ (p. 134) Wikipedia

currently references a text by G. Pascoe and P. Pepper (see footnote 1) where the authors pick up on this theory by Weddell,

and state that Jewitt did not receive orders to claim the islands at his

departure from Buenos Aires, contradicting what other references state. Despite

them claiming that there is ‘much evidence’, they offer no more support than an account of other business performed by Jewitt before

landing on the islands, which would only imply a lack of urgency, and that his

ship was in bad shape when he did, as asserted by Weddell, which only gives

way to a suspicion. In any case, it would not be legally significant if Jewitt

had not received those orders. In response to doubts about the authority of the

government that (presumably) sent Jewitt, Gustafson argues, on page 22 of his

book10, that ‘at the very least, Jewitt had publicly

claimed possession in the name of Argentina, whose government could later

confirm or deny his claim. The government would confirm Jewitt's claim.’ Let us

bear in mind that commissioned sailors normally claimed islands, that they

discovered, in the name of states that did not know about the islands at the

time of their appointment.

[9] Fitzroy, in his Narrative

. . ., vol 2 (see footnote 4), mentions Jewitt’s proclaim under the Argentine flag

(p. 236), offering Weddell’s book as a reference, but he says that the act was

unknown in Britain

for many years and only noticed formally in 1829. However, it is known

that this news was published in European newspapers. Besides,

Weddell’s book was published in 1825 and, given his official position, he must

have informed his superiors beforehand.

[10] Gustafson,

L. S.; “Historical Rights”; The

Sovereignty Dispute over the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands; Oxford University

Press, Oxford, U.K.; 1988

[11] Hope, A. F. J.;

“Sovereignty and Decolonization of the Malvinas (Falkland) Islands”; Boston College International and Comparative Law Review;

Vol. 6, Issue 2, Art. 3; (1983); pp. 413–414

[12] ‘Upon acquiring independence, a former colony

ordinarily inherits all the territory of that colony. This principle, enshrined

in Latin America and, a century later, in Africa, would certainly appear to

apply to the Falklands. Spain treated

the islands as part of the Vice-Royalty of Buenos Aires, and did not occupy

them [after the revolution]. Moreover, the short time that elapsed before Argentina

took control of the islands does not seem to warrant the conclusion that Argentina was

derelict, thereby transforming the territory into a res nullius. International

law has traditionally tolerated temporary lapses in the control of central authorities

over peripheral territories caused by internal disruptions.’ Reisman, W. M.; “The

Struggle for The Falklands”; Faculty Scholarship Series; Yale Law School,

New Haven, CT; 1983; p. 303. Not to be confused with Goebel’s book of the same

name. It has

been argued (see footnote 1) that, under uti possidetis juris, Chile or Paraguay

would be as entitled as Argentina

to the islands, because they also emerged from the Spanish colony. However,

given the islands' geographical proximity to Argentina, it would be unnatural to

assign them to those other nations, and a risk of war. Vernet makes this point

in his 1832 report. Presumably due to this reasoning, those nations did not

claim them.

[13] Gustafson, p. 22

[14] It is said (see footnote 1) that Vernet had gotten permission from the UK to build his colony, but the only support

that I found for this assertion is that the British Vice-Consul in Buenos Aires may have countersigned, on Vernet's request, the land grant that the latter obtained from Buenos Aires

in 1828. I could not verify this fact, neither I found comments about it in

authoritative literature, but if the Vice-Consul did in fact countersign, it

would not imply that Vernet, or the Consulate, understood that the UK was entitled

to decide on such grants. Actually, the opposite could be interpreted, because

countersigning means validating a document, although they may have only been

confirming its authenticity. It was also suggested that Vernet was considering

that his colony may fall into British hands, and even welcoming it. Again, that

would not mean that he attributed rights to Britain,

because he may have been anticipating a cession (sale) from Argentina, or a high-handed act from the UK. If it was

genuine, a British preference of his part would be understandable, given that Britain

commanded the world’s most powerful navy, but in no way it undermines his acts

in support of the Argentine case, nor it contradicts the defense of Argentine rights

that he wrote in 1832 (see footnote 17).

[15] Vernet,

L.; Report of the Political and Military

Commandant of Malvinas to the Chargé d’Affairs of the United States, 10th

August 1832; in Great Britain. Foreign and Commonwealth Office; British and Foreign State Papers, Vol. 20, 1832–1833; James Ridgway

and Sons, Picadilly, U.K.; pp. 369–436

[17] In other contemporary documents (e.g., footnote 15), the state and Vernet refer to his title

indistinctively as ‘Civic and Military Commandant’ or ‘Civic and Military

Governor’, and so do modern references. I doubt the choice makes any difference

in relation to the dispute.

[18] Vernet, p. 380

[19] Peterson, H. F.; Argentina and the United States, 1810–1960; University Publishers,

State University of New York, NY; 1964; p. 104. Click

here for a preview.

[20] FitzRoy writes, in pages 271–272 of his book, 'I went to Port Louis, but was indeed disappointed. Instead of the cheerful little village I once anticipated finding—a few half-ruined stone cottages; some straggling huts built of turf; two or three stove boats; some broken ground where gardens had been, and where a few cabbages or potatoes still grew; some sheep and goats; a few long-legged pigs; some horses and cows; with here and there a miserable-looking human being,—were scattered over the foreground of a view which had dark clouds, ragged-topped hills, and a wild waste of moorland to fill up the distance. “How is this?” said I, in astonishment, to Mr. Brisbane; “I thought Mr. Vernet’s colony was a thriving and happy settlement. Where are the inhabitants? The place seems deserted as well as ruined.” “Indeed, Sir, it was flourishing,” said he, “but the Lexington ruined it: Captain Duncan’s men did such harm to the houses and gardens. I was myself treated as a pirate—rowed stern foremost on board the Lexington—abused on her quarter-deck most violently by Captain Duncan—treated by him more like a wild beast than a human being—and from that time guarded as a felon, until I was released by order of Commodore Rogers.” “But,” I said, “where are the rest of the settlers? I see but half a dozen, of whom two are old black women; where are the gauchos who kill the cattle?” “Sir, they are all in the country. They have been so much alarmed by what has occurred, and they dread the appearance of a ship of war so much, that they keep out of the way till they know what she is going to do.” I afterwards interrogated an old German, while Brisbane was out of sight, and after him a young native of Buenos Ayres, who both corroborated Brisbane’s account.'

[21] Adams, J. Q.; Memoirs of John Quincy Adams,: Comprising

Portions of His Diary from 1795 to 1848, Vol. 9; Lippincot & Co.,

PA, p.447; 1876. Evidently, the incapability of Argentina,

alleged expressively by Adams, refers to her authorities not being able to

pursue her case further, exposing Baylies and the U.S. in the process. There is no reason to believe

that Baylies was under risk of ‘indelible disgrace’ from which he could have

been saved by Argentina’s

defense of Vernet. As I understand it, Adams was expressing some support to

the Argentine position in the Lexington

incident, despite the harsh language he used. Additionally, Goebel (cited by

Hope, p. 415) mentions a salvage action for the seal skins seized by Vernet,

presented to the Circuit Court of Connecticut, that failed because the court

considered that the islands were under the authority of another state, which

was Buenos Aires according to him: ‘Captain Duncan could have no right, without

express' directions from his government, to enter into the territorial

jurisdiction of a country at peace with the United States, and forcibly seize

upon the property found there and claimed by citizens of the United States.’

Davison v. Seal-Skins, 7 F. Cas. 192, 196 (C.C.D. Conn. 1835) (No. 3661). This contradicted Baylies' defense of Duncan when he argued that the islands were res nullius.

[22] Greenhow,

R.; “The Falkland Islands”; Hunt’s Merchants’ Magazine, vol. 6 (1842); pp.

104–151. In his defense to Slacum’s offices, Greenhow claimed that Buenos Aires expressed too late that Vernet acted under

official orders, only after the Lexington

had sailed, and that the fishing regulations were unjustified. He also

minimizes the damage done by Duncan and his crew, suggesting that British

accounts exaggerate them because of an anti-American sentiment. Goebel, who

examined the log of the Lexington, writes ‘It is

curious that there is no notice of any of these transactions in the log-book of

the Lexington.

Perhaps Duncan

was a little ashamed of what he had done, or perhaps he feared the effect his

actions would have upon his government.’ (Goebel, The Struggle for the Falklands, footnote 20, pp. 444–45, cited by

Hope, footnote 60, p. 415)